Over thousands of years of living and traveling on the ocean and inland waterways of what we now call Maine and the Maritime Provinces, the Wabanaki people developed a highly evolved, perfectly adapted type of birchbark canoe for this area. Wabanaki, or “People of the Dawnland,” is the collective designation given to the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, Mi’kmaq, and Abenaki tribes. Historically, many of them spent at least part of their time on the seacoast, especially before European contact.

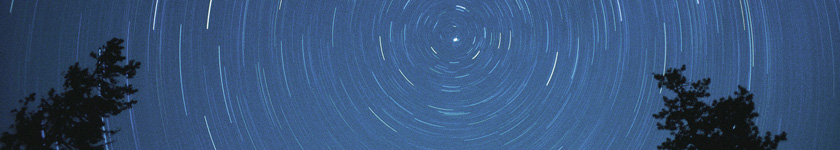

Passamaquoddy Canoe built by Sylvester Gabriel (Passamaquoddy), en route from Pleasant Point to Plymouth, Massachussetts, for the Plymouth tri-centenial, 1921. Paddlers are William Neptune and Horace Nicholas.

Passamaquoddy Canoe built by Sylvester Gabriel (Passamaquoddy), en route from Pleasant Point to Plymouth, Massachussetts, for the Plymouth tri-centenial, 1921. Paddlers are William Neptune and Horace Nicholas.Accordingly, the hulls of their canoes were very seaworthy, designed for maximum buoyancy in the ends and reserve buoyancy in the sides, for use in rough water conditions. They had canoes built specifically for ocean use, with greater depth and rocker than in canoes used primarily on fresh water. Yet even river and lake canoes retained the basic hull-form of the ocean canoes, because any of them could and would at times be taken downriver to salt water on occasion. Their seaworthiness also served them well on the big lakes of the interior. Another reflection of the maritime origins of these canoes is the high level of craftsmanship and attention to detail that is typical in their construction. This was likely due to the stable food source that the ocean represented, which freed up more time for the development of the canoe builders’ skill and artistry.

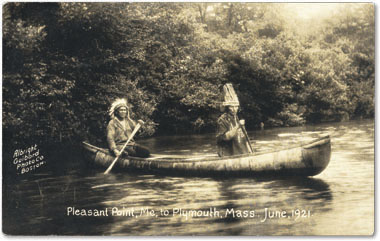

Montagnais birchbark canoe building, north shore of St. Lawrence, ca. 1863, Alexander Henderson, New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, NB CPF-F26-1, copy photo, original at Library and Archives Canada.

Montagnais birchbark canoe building, north shore of St. Lawrence, ca. 1863, Alexander Henderson, New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, NB CPF-F26-1, copy photo, original at Library and Archives Canada.The Wabanaki homeland is also by nature densely forested, and so for thousands of years its people relied on the birchbark canoe as their chief method of transportation, using the rivers and lakes, as well as the coastal routes, to form an ancient “superhighway” system, not only for seasonal, subsistence-based movement, but also to travel vast distances for purposes of trading and of building intertribal alliances.

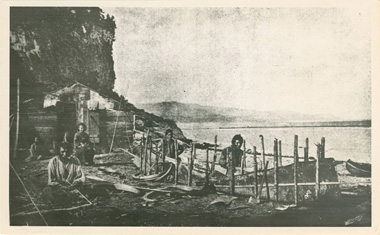

Wolastoqew Guide and Canoe, New Brunswick, c. 1862, George Thomas Taylor, New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, N.B. 1987.17.413, William Francis Ganong collection

Wolastoqew Guide and Canoe, New Brunswick, c. 1862, George Thomas Taylor, New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, N.B. 1987.17.413, William Francis Ganong collectionMy research and canoe building focuses primarily on the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and Maliseet of Maine and New Brunswick, who as a result of their close intertribal ties, share a distinctive and graceful traditional style of birchbark canoe, with little if any difference between the canoes of these three tribes. Most of their canoes did, however, go through some changes in style during the course of the 19th century, particularly noticeable in the end profiles.

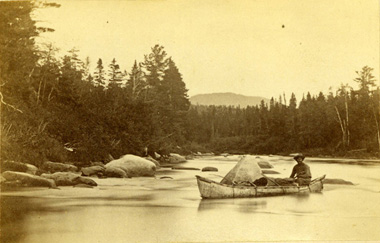

Wolastoqew Guides and Canoes along the Tobique River, New Brunswick, c. 1862, George Thomas Taylor, New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, N.B. 1987.17.418, William Francis Ganong collection

Wolastoqew Guides and Canoes along the Tobique River, New Brunswick, c. 1862, George Thomas Taylor, New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, N.B. 1987.17.418, William Francis Ganong collectionIn the early1800’s and before, they had sharp, raking end profiles, which placed the extreme ends of the canoe at the top of the stems. The ends of canoes from the late 1800’s were generally re-curved, so that the extreme end measurement fell partway down the stems. This later style appears to have spread from west to east, beginning with the Abenaki, then adopted by the Penobscot, and reaching the Passamaquoddy and Maliseet last.

Wolastoqew Men and Canoes above Arthurette, New Brunswick, c. 1862, George Thomas Taylor, New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, N.B. 1987.17.538, William Francis Ganong collection.

Wolastoqew Men and Canoes above Arthurette, New Brunswick, c. 1862, George Thomas Taylor, New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, N.B. 1987.17.538, William Francis Ganong collection.

Wolastoqew Men Poling Canoes on the Tobique River, New Brunswick, c. 1862, George Thomas Taylor, New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, N.B. LS-A18, New Brunswick Museum Collection

Wolastoqew Men Poling Canoes on the Tobique River, New Brunswick, c. 1862, George Thomas Taylor, New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, N.B. LS-A18, New Brunswick Museum CollectionThe ends of the older form also tended to be higher, which facilitated the common practice of turning the canoe over to use as shelter for the night when traveling. This could only be done with the later low-ended style with the aid of forked sticks used as props under the gunwale to gain more headroom. These later canoes were also usually fastened at the gunwales with nails or screws rather than with roots and pegs, and the sewing in the bark was often done with rattan chair-caning instead of root strands.

Outlet of Green River Lake, near Edmundston, N.B., 1887, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick George Taylor fonds P5-134-B.

Outlet of Green River Lake, near Edmundston, N.B., 1887, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick George Taylor fonds P5-134-B.From the mid-19th century, when Henry David Thoreau explored the Maine woods in birchbark canoes with the help of Penobscot guides, until the early 20th century, when wood and canvas canoes became popular, birchbark canoes were used widely by natives and non-natives alike for hunting, fishing, and sightseeing.

Portaging a canoe at Green River, near Edmundston, N.B., 1887, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick George Taylor fonds P5-137

Portaging a canoe at Green River, near Edmundston, N.B., 1887, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick George Taylor fonds P5-137In fact the early canvas canoes built by Old Town, E. M. White, Chestnut, and others were modeled closely after the local Wabanaki canoes, and thus by extension the birchbark canoes of Maine and New Brunswick can be said to be direct ancestors to most modern canoes. Their shape is generally familiar to canoeists for this reason, more so than, for example, the Great Lakes area canoes, such as the Fur Trade canoes with their high end structures and flared sides.

Camp at Tobique Narrows, c.1862, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick George Taylor fonds P5-248

Camp at Tobique Narrows, c.1862, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick George Taylor fonds P5-248For all their historical importance, the Wabanaki canoes are not well documented in their own right, though it is my goal to help fill that gap. By far the most significant record to date was compiled through the efforts of E. Tappan Adney, as represented in the book The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America by Adney and Chapelle, as well as in the over 130 scale canoe models made by Adney, most of which are in the collection of The Mariners’ Museum, in Newport News, Virginia. Adney’s record is an excellent overview of the different tribal styles and their construction.

Temiscouata Lake, Quebec, c. 1865, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick George Taylor fonds P5-598-R

Temiscouata Lake, Quebec, c. 1865, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick George Taylor fonds P5-598-RTo see larger versions of these photos of Maliseet canoes, click here.

Outstanding compilations of historical photos of Maliseet people and their canoes can be found on the following websites:

Wolastoqiyik - Portrait of a People

An exhibition of photos and drawings of Maliseet history and culture, including birchbark canoes.

Wolastoqiyik, Mi'kmaq, and Passamaquoddy Peoples

A collection of historic photos of Wabanaki subjects, including birchbark canoes, from the New Brunswick Museum.

Also, see the Links Page for additional resources